What happens to people displaced from their neighborhoods by eminent domain? While residents of St. Louis Place in north St. Louis fought to keep their homes, the city offered up their land for a new development project. This has happened before, says historian Margaret Garb.

This summer, the city of St. Louis knocked down several dozen houses in St. Louis Place, a century-old neighborhood just north of downtown. The 99-acre site, once a working-class black neighborhood, is destined to become the home of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, which is moving from its outdated offices south of the city. With $1.6 billion in federal dollars and more than 3,000 jobs at stake, St. Louis fought hard to keep the agency in the city.

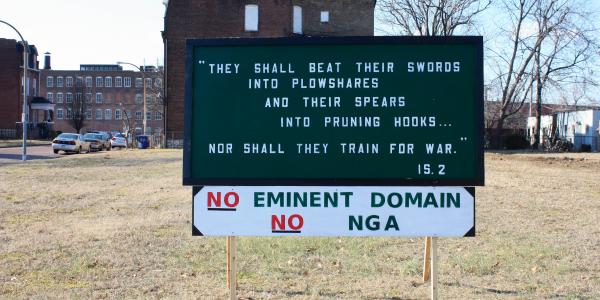

But many residents were angered and disappointed that city officials determined to replace their community with high-tech office buildings surrounded by parking lots and a high-security fence. Some long-time residents refused to sell their homes and businesses.

The city owned some abandoned properties, and dozens of parcels were held by developer Paul McKee, who stood to profit from the sales. The city purchased 551 parcels with just 136 intact buildings; 88 were inhabited houses or businesses, according to a St. Louis Post-Dispatch story. The city used eminent domain to acquire 44 buildings.

Eminent domain gives the government legal right to take private property for public use or to serve a public good. The government is required to compensate property owners at fair market value, which often is disputed. Even more controversial is the definition of the “public good.” Government has taken private property for the construction of schools, post offices and national parks. In the 2005 Kelo case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that government can seize private property for a private business in an effort to boost tax revenues and economic development.

Who counts as the public and what counts as a public good are hardly settled issues. The courts have given municipalities expansive authority in eminent domain cases. All too often, the public good is equated with enhancing property values and filling government treasuries while officials downgrade the interests of poor and African-American communities.

This summer’s rapid acquisition of land and housing in a struggling African-American neighborhood proved a grim reminder of urban renewal, the federal government’s mid 20th-century slum-clearance program that tore down working-class white and black neighborhoods in many major cities. With urban renewal, whole communities were displaced and erased from local history.

Urban renewal’s early advocates believed the program would replace run-down tenements with modern housing and glass-sheathed office buildings. More often, cities got sports stadiums and urban malls while low-income residents were moved into high-rise public housing. Poverty was shifted from one neighborhood to another. The historian Arnold R. Hirsch called the “renewal” of Chicago’s south side, the “making of the second ghetto.” James Baldwin called it “Negro removal.”

A familiar process: Mill Creek Valley

St. Louis had a particularly rough urban renewal experience, which explains the alarm of long-time residents watching the demolition of St. Louis Place. Mill Creek Valley, a neighborhood of 20,000 families stretching through the city’s core, was flattened in the early 1960s. The neighborhood, one of the few open to African Americans under the city’s segregation codes, was home to black teachers, janitors, cooks, laundresses, railroad porters and musicians. There were shops, grocery stores, churches, saloons and a bank owned by African-American investors. The Booker T. Washington Theatre featured performances by Josephine Baker, Eubie Blake and Bessie Smith.

The People’s Finance Corporation Building included a ballroom, NAACP offices, a music studio, and offices of black doctors and lawyers. The People’s Bank, on the first floor, was one of the few banks willing to provide housing and small business loans to African Americans. The St. Louis Argus called the building “one of the outstanding accomplishments” of black St. Louisans.

But racial segregation crippled the community, pushing up rents and leading to deteriorated housing. A residential survey in 1958 found that more than half of the dwellings lacked indoor plumbing. Rats were a regular menace.

On August 7, 1954, Mayor Raymond R. Tucker announced plans to demolish the commercial buildings and 5,600 residential units in Mill Creek Valley. His hope was that after the land was cleared, private investment would build a new modern neighborhood. Newspapers praised Tucker’s “bold vision.” The local NAACP supported the plan. City voters approved a $10 million bond issue to raze the neighborhood. It became one of the nation’s largest urban renewal projects.Tucker’s plan, coming as the city’s population peaked in 1950 at 856,796 people, was based on assumptions of continued population growth. That proved a mistake. Reinvestment was slow or not at all. The clearing left a vast wasteland that St. Louisans called “Hiroshima Flats.”

Urban renewal left a conflicted and contradictory legacy, highlighting the racism imbedded in federal housing programs, throwing blame on some well-intentioned planners and public officials, and ultimately discouraging government investment that many cities and poor neighborhoods desperately needed in the late 20th century.

Mill Creek Valley today is ballfields, a college sports stadium, Harris-Stowe State University, highway entrance ramps and an office park owned by an investment bank. It is St. Louis’ most famous forgotten neighborhood.

The process through which the Mill Creek Valley disappeared from the landscape and from the city’s collective memory was itself complex. That process of forgetting is also part of St. Louis’ history.

Eminent domain, a seemingly obscure legal tool, has pushed whole communities out of our collective memory. Americans commemorate some historic places. But we rarely recognize the urban neighborhoods that were forged under the weight of segregation, molded into vibrant working-class communities and then demolished. As we continue a long American tradition of debating the public good, we could commemorate the neighborhoods erased from the landscape, the places that once were the hearts of American cities.